The agrarian disposition of the people of Cross River State has, over the years, made land tussle a recurring decimal, especially during the onset of the rains, which signals the commencement of the farming season. Yet, unending inter-communal conflicts are exacerbating rural poverty, threatening household incomes, as well as telling on the food production profile of the state and food security, TINA AGOSI TODO reports.

With land as the mainstay of the local economy, recurring inter-communal clashes over land disputes not only exacerbate ethnic tensions but also disrupt the livelihoods of the citizens, in addition to causing dislocation in the agro-allied businesses value chain. Ultimately, this predisposes people to food insecurity among other things.

In agrarian communities, the arrival of the rainy season is celebrated as it signals the commencement of the farming season. But in recent years, this period has been marred by an unfortunate recurring decimal – communal conflicts – in some communities in Cross River State, and this menace revolves around land and access to cultivable land, thereby threatening farming that has sustained hundreds of thousands of families across the state.

Despite the much-vaunted efforts of the government, these communal conflicts have continually occurred to the point that many fear that failure to contain them may cause the deletion of the state as one of the country’s major staple food producers. Importantly, however, such a development will also adversely impact poverty reduction efforts in the state, posing a serious threat to food security.

The cyclical bloodletting during the wet season is buttressed by records from the Cross River State Emergency Management Agency (SEMA), which show that communal hostilities over farmlands are prevalent in 16 out of the 18 local councils of the state.

Some of the local councils affected by communal hostilities over farmlands at one time or other leading to loss of lives and property are: Abi, Akamkpa, Biase, Bekwarra, Boki, Odukpani, Obubra, Ikom, Etung, Obanliku, Obudu, Yakurr, and Yala.

Of Nigeria’s 36 states, Cross River State, which is the 19th largest, has a population of approximately four million people (as per a 2016 official figure). Located in the coastal region of the Niger Delta, the state’s 20,156 square kilometres comprises fertile land that is suitable for one form of agriculture or the other.

The state is also endowed with abundant, valuable, and rich mineral resources, in addition to having a huge potential for tourism development. However, agriculture remains the predominant occupation of the people, with more than 70 per cent of its population engaged in subsistence and large-scale farming.

Although different factors such as politics, environment, and ethnic dichotomies have been identified to be responsible for these communal hostilities, investigations reveal that the agrarian disposition of the people, which has, over the years, made land tussle among individuals and communities a recurrent decimal, accounts largely for the greater proportion of communal clashes, resulting in low food production, supply, and distribution in the state.

According to research, between 2012 and 2013, with two notable peaks in the first half of 2012, and the first half of 2013 overall, 47 violent incidents reportedly led to the deaths of many, even as several communities have lost their ancestral homes and are scattered in neighboring communities.

In the course of these conflicts, farmlands, schools, places of worship, markets, clinics, and sundry public institutions were razed down, and indigenes of some of these communities could not go back to these structures after the crises for fear of being killed.

A chronicle of these ugly incidents indicates that in Abi Local Council, long-standing land disputes in most of the communities sometimes turn into violence leaving so many dead. Usumotong and Ediba communities have farmland boundary disputes that have been on for decades.

In a 2006 land tussle, the Ebijakara Community was sacked by their Ebom neighbours. Even though fragile peace has since been restored, the communities constantly feud over unresolved land skirmishes, which assume violent dimensions during farming seasons.

Onyadama and Inyima communities have been at war since April 2016. Adadama, a community in Abi Local Council, and Ameagu Community in Ikwo Local Council of Ebonyi State have conflicted for many years over a piece of land, which several lives have been lost and property worth millions of naira destroyed.

Odukpani Local Council has had her fair share of inter-communal land disputes with a community in Itu Local Council of neighboring Akwa Ibom State clashing with the people of Odukpani, leading to the destruction of farmlands, and houses and killing people.

In Yakurr Local Council, the people of Mkpani and Nko have, over the years been engaged in endless crises over land issues. Last October, two communities in Obubra Local Council- Ovonum and Ofatura were locked in a conflict over a parcel of farmland, and the feud left many dead, and over 300 houses destroyed.

Wanehim and Wanakade in Yala Local Council, as well as Kutia and Okwotung communities in Obudu Local Council, have all been at war over farmlands. Oruagbam and Abanwan in Biase have become wasted lands as a result of communal conflicts.

In March 2023, the conflict that broke out between the people of Ofunokpan-Mbembe and Ntansele in Ikom Local Council of the state allegedly claimed three teenage lives.

Both communities have been at each other’s throats for over 30 years, and the serial conflict has led to the loss of several lives and the destruction of farmlands.

The conflict started in 1993 when the Ntansele people attacked Ofunokpan-Mbembe and chased them out of their ancestral land. Since then, both communities have not known peace.

One of the aggrieved youths from the Ofunokpan-Mbembe Community, Saviour Nse said: “The youths are frustrated with what is happening because most of us are farmers. We want to claim our land back because we have suffered for over 30 years.”

With only a handful of these conflicts in the state linked to boundary-related matters, the bulk of them are farmland-induced, and this explains why they keep on reoccurring during the onset of the farming season.

Consequently, the state, which has been a dependable source of food supply churning out a variety of fruits, vegetables, as well as yam, cassava, plantain, rice, cocoa, oil palm, rubber, etc., at both subsistence and commercial levels is gradually failing to live up to expectations.

Speaking on the persistent communal clashes in the state and their impact on food production and food security, farmers from a few of the warring communities explained that these conflicts have brought untold hardship to the livelihoods of the warring communities and the state economy.

A farmer, Odey Augustine, while speaking on the persistent communal clashes in the state and its impact on food production and food security said that a lasting solution should be proffered for the crises to stem the loss of resources.

Augustine whose Ijiego-Yache Community in Yala Local Council has conflicted with a community in neighboring Benue State said: “A lot of our rural dwellers lost their pepper farms during the crisis that happened early this year. This is when we are supposed to be planting groundnut, which we would have harvested in 90 days, but that will not happen.

“We are supposed to be cultivating groundnuts, cassava, yam, and garden egg, but we don’t have seedlings to go back to the farm. We are one of the communities that contribute between 40 to 60 per cent of the agricultural produce from the state. The pepper you see in Calabar, Enugu, Onitsha, and several parts of the East are from here, but right now, most of the farmers have not started planting this year.”

He continued: “All the schools in the community were shut down for the whole of the second term. Consequently, our over 2,000 children did not attend school because of insecurity,” Odey lamented.

“In Obubra Local Council, where we are temporarily settled, we buy land at between N15,000 and N50,000 per season just to plant and survive. For how long shall we continue to live in a strange community and be buying land to build and farm?” Nse questioned.

According to the Paramount Ruler of Abi Local Council and Clan Head of Usumutong Community, His Royal Majesty, Ovai Edward Osim said: “In Abi Local Government where I come from, Usumutong and Ediba Ebom and Ebijeakara, Adadama and Iku, a boundary community in Ebonyi State are the communities that always experience crises during the farming season.

“It will affect food security because people are not free to engage in full-scale farming; they go to the farm under fear, and are most times afraid to enter the bushes for fear of being attacked and killed.”

Bassey Akpang, from Ediba Community in Abi Local Council, explained: “This ugly development has affected all the nine communities in the Bahumono Nation. We are known for large-scale rice, garri, and palm oil production. There’s a major market in Ediba Community, which serves as an off-takers evacuation point for virtually all the other communities.

“For several years this market has been almost completely desolate as a result of the communal crisis. Farmers no longer go to farms freely for fear of being attacked. So, the situation has impacted negatively on our livelihood as farmers.”

Monday Uba, from Ebom Community, also stated: “For the past three to four years, we have not had any crisis, but during the time of communal crises between us and Ebijekara, people don’t go to farm because most of our major farmlands were seized by them and theirs seized by us. We used to sneak to the farm. We produce palm oil, groundnut, cassava, garri, and the rest. On our market days, people come to our community to buy these goods.

“In most cases, the state government through the Office of the Deputy Governor initiates peace talks, but once the wet season approaches, the war drum gets beaten again. This could be because the state government has not done enough to find a lasting solution to the seasonal clashes,” Uba said.

He continued: “On several occasions, the state government has taken steps to authenticate the ownership of the land in dispute. But amidst all these crises, the government is slow in releasing the White Papers, and even when they are released, they are usually not fully implemented. So, that has kept the dispute lingering for years.

“We are not happy because we have been deceived by past governments that we would soon be settled. We need the implementation of the White Papers, or else we will go and die there; it is our father’s land,” Nse vowed.

“We have been calling for peace and we expected more support from the government, which needs to wade in. The white papers that were issued during the time of Donald Duke, and Liyel Imoke are yet to be implemented. If they were implemented, it would restore peace in these troubled communities,” he added.

“A Judiciary Commission of Enquiry has always been set up by the government, and there is always a white paper arising from the meetings, but in the end, these papers are not implemented for years. This attitude of government does not encourage peace. So, we urge the state government to ensure that the white papers are fully implemented. That is the only way peace can be restored,” Ovai Osim added.

On his part, the former Chairman Association of Farmers, Cross River State Chapter, Owen Oyama said: “Land does not grow, but human population expands. So, the challenge that we have is for indigenous communities to understand that the plots of land that they inherited from their forefathers have not shifted an inch; it’s that same land. So, these communities must look for other alternative means to accommodate everybody.

“During my tenure as the chairman of the farmers association in Cross River, I told the former governor, Senator Ben Ayade, that there should be alternative livelihood to make up for the loss of farmlands, and that the government should make efforts to make this come to past. Also, for cluster communities that don’t have enough land, a means should be devised to train them in other skills of livelihood, but not politics. This administration should consider that,” he opined.

The state Commissioner for Crops and Irrigation Development, Johnson Ebokpo, in an interview with The Guardian, attributed 90 per cent of communal conflicts to low productivity, noting that the efforts around those communities are smallholder in nature.

He said that the state government’s new approach to tackling some of these issues is the initiation of reforms in the agricultural sector that would benefit smallholder farmers across the 18 local councils, including the warring communities that have lost their farmlands, noting that when communities start producing optimally, communal clashes would diminished.

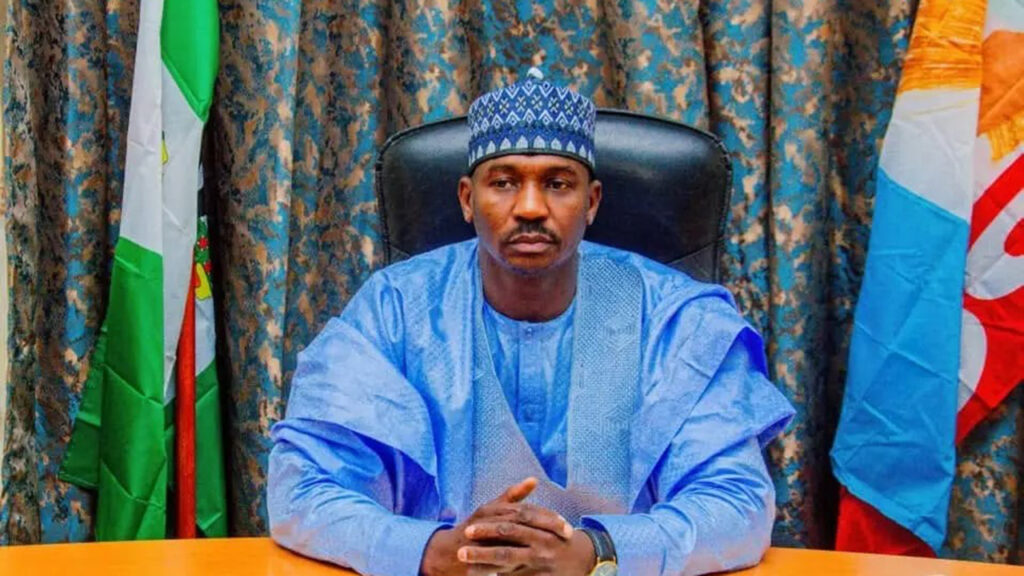

Ebokpo said: “Senator Bassey Otu is initiating reforms, and in the next two to three years, you will be looking for communal clashes to cover, but you won’t see any, only the manifestation of the reforms. So, his approach is very innovative; it is different from the norm, and what you have always been used to. Having considered all the steps that were taken in the past, we are focused on the reforms.

“So, the moment we begin to throw levers that drive productivity, we will begin to see communal conflicts diminishing; people will settle rifts by themselves because there is something at stake.”

According to him, part of the strategic plan that the government is developing, which would benefit all farmers in the state is the cultivation of cocoa, oil palm, and coffee, adding that the ministry has introduced the concept of wheat, which he said is a key factor for feed production, millet, sorghum and the value chain around groundnuts would be scaled up.

Several attempts to speak with the Department of Conflict and Resolution, operating under the office of the Deputy Governor of Cross River State, Peter Odey proved abortive.