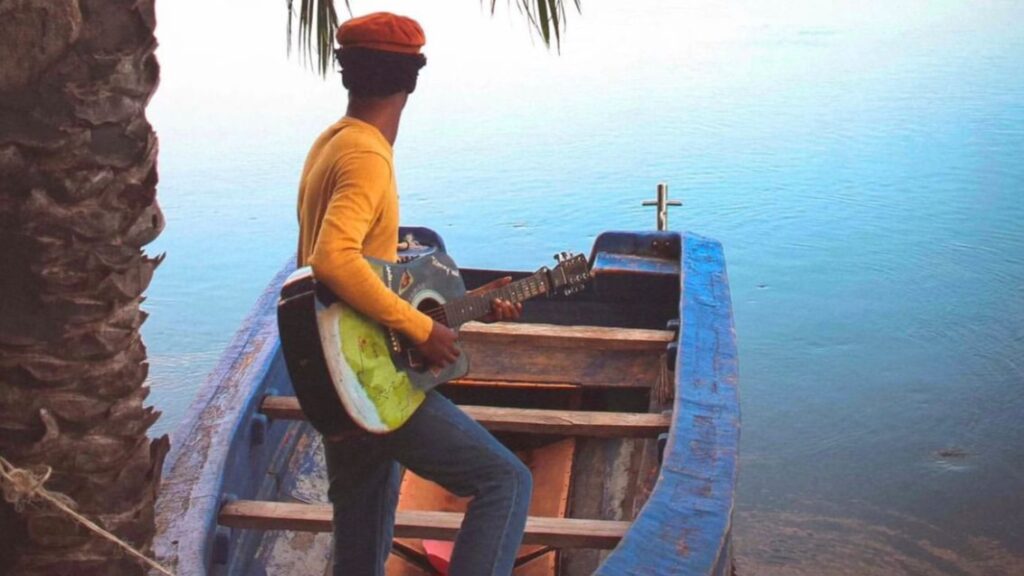

When Oluwatomiwa Suleman – the method maverick known as Tommy Wá- emerged, in 2016, the Nigerian music scene was not ready for it. Soothing ballad-like folk fusions, rebelliously encrypted in guitar riffs that serenaded human-centered themes were the easiest markers to distinguish Tommy Wá. And, till date, the young musician, based in the bustling coastal city of Accra, continues to travel those uncommon routes, with the pride of being African.

When Oluwatomiwa Suleman – the method maverick known as Tommy Wá- emerged, in 2016, the Nigerian music scene was not ready for it. Soothing ballad-like folk fusions, rebelliously encrypted in guitar riffs that serenaded human-centered themes were the easiest markers to distinguish Tommy Wá. And, till date, the young musician, based in the bustling coastal city of Accra, continues to travel those uncommon routes, with the pride of being African.

Born to Nigerian parents, and shuttling his childhood across Abuja and Ibadan, Tommy Wá honed a very niche taste in music from a tender age. While the rusty sonics of vintage Afro Pop seized the airwaves, side-by-side with American RnB, in the ‘90s and early 2000s, Tommy Wà prudently sought solace in the wonders of Juju Legend King Sunny Ade, American funk hero James Brown, American folk icon Bon Iver, and other Nigerian heroes like Lagbaja, and Asa, respectively. The result? A folk diet that echoes with deeper soul and more clear-headed poetry. An eight-year-old discography that shines through every step of its evolution, from 2016’s 4-tracker Me and Me, 2019’s ‘Come and Go’, 2021’s ‘Gravity’, and 2023’s 7-tracker comeback, Roadman and Folks.

With Tommy Wà’s artistry, one can relish in the low-hanging fruits of stellar musicianship. The indie-singer who’s worn a hat as a photographer, in previous years, effortlessly projects a snapshot of human reality through his music. His Living Room Tour live renditions are among the myriad evidence of his remarkable talent. And, when he sings, the music ages like food for thought, and spirit.

In a sit-down with Guardian Music, the guitar-wielding maestro peels off several layers behind his identity, unmasking the journey to becoming Tommy Wá, his sonic influences, life as a folk artist, as well as his vision of pursuing meaning and building a hunger in all of us to do the same.

Take us to the beginning of when you became Tommy Wa.

I think I was talking about this with my dad yesterday that it had to do with 2016, when I had decided I wanted to be a recording musician. I had always had love for performance and that was what I did and thought I was going to be- performer and an artist. But in 2016, I had this epiphany to get into music recording and off the back of that was all the influences I have had in the last three years of having experienced music. And some of the sounds I was listening to, back then, in the space of 2012 to 2016, was mostly Indie music, folk, American alternative. But prior to that, I had an understanding of African folk, you know, Ebenezer Obey, Sunny Ade for his guitar skills, presentation wise, his swag, all those things. All of that put together, with the Indie folk, and the American side, coupled with what was already available to me from my Yoruba fellows, you know, the folk artists that could sing about anything and still make it African.

So, I think at some point, I had come to a round circle in 2016, to express myself freely. But I wanted to take the sound further and cool it properly. In reality, as a kid that grew up in Ibadan, we listened to both western radios, and Yoruba radio. So, I was like what sound will make sense to people that experience my reality? And I was like it’s this sound that I am doing right now, which in many ways the soundscape has been called Afro Indi. But that’s for industry. The real sense of it is what is Tommy Wa’s reality, what is the reality of a kid that grew up in Ibadan, that grew up in wester Nigeria, even Abuja but was not exposed to afrobeat, the intensity of that Yoruba speaking, but had a flavor and desire for western music, but was still African. So, I guess these were the things that guided me to create the sound that I was creating. I’m originally a guitarist, a vocalist and a songwriter, but in the way I “cook” these sounds, I wanted it to be whatever sort of expression, but coming from an African.

What is your usual creative process when you want to make a project?

It’s different for every project, right. There’s some that is very impulsive and I just get into the studio and make the songs in two weeks. Whether I have it finished or not, I just make the songs and we have the project. But for this recent one, Roadman and Folks, I have been living the life of what I have been doing, of what is in this music now. I have been traveling, I have been going to different cities, I have been playing gigs in different countries, I have also been experiencing life in different ways. So, I have been jutting all those things down, putting them down in note. I think the only latest written song on this current project was written last year. No song was written this year. So, in many ways, it wasn’t impulsive. It was a gradual process of collecting data. I have this thing on my note called flash thoughts. So, collecting data, flash thoughts, and putting them together first of all. It’s a puzzle system, I call it a puzzle system of writing, and before I know it, I have instruments or guitar riffs that are interesting to me and I form them. I compose the guitar, the melodies. And when we get into the studio, for a song like Yakoyo, I compose the guitar melodies, I compose the base melodies, then I just tell everybody that I need to be on the production side. Like, this is what I kind of want, and then let’s couple these words together and then that was how we made this project.

Why did you decide to title it Roadman and Folks?

Roadman and Folks, was originally a business organization that I was setting up, or still setting up. So, Roadman and Folks, I started this company back in 2020, when we were off cycling hats. We would go to the market, buy hats, like the ones I wear, and then we would upcycle them and resell them. We call them “dead white men’s clothes.” So, we would resell them and then it started as a business and I used to call it Roadman and Folks. And I started a playlist and I started to see my life and my music more from an entrepreneur’s point of view. And through this art, I was already starting to guard that community. I was the road mine, figuring that community, knowing where to get this, knowing where to get that. As an independent artist, it made sense that I needed to enterprise what I was doing. Who were the people that were going to buy these things? My folks. But on a bigger level, it was more about Roadman and Folks, me serving my community and my community also serving me to a point of sustainability. And when it came to naming the project, it just made sense that okay, from the Roadman and Folks company, this is our first project that we are putting out and establishing and immortalizing the community that dwells around me and listen to my music and buy my stuff, then I serve. So, this was my own way of immortalizing that community in Accra, Lagos, Abuja, in Kumasi where I schooled, in all the places where I have played at. So, yeah, this is my own way of thinking that I could immortalize this- Roadman and Folks.

Who are some of the other contemporary players in this scene that you admire their works and possibly like to collaborate with?

The great thing about being, as you called it, niched is that you can collaborate with anybody. I don’t necessarily see myself tied down. If the people have the vision and the sense of collaboration, I don’t see myself within just my own community. I could sing on a Sarz beat, funny enough. I could sing on a Mr. Eazi beat. Mr. Eazi specifically is one person I would love to collaborate with. He is retired now, so that’s funny. But we have people like Obongjayar, Childish Gambino. I love the kind of music he is putting out. Britney Howard, but she is not Nigerian, she’s American from Alabama. So, these are some of the people that I would love to collaborate with.

Within the Nigerian scene or Ghanaian?

To be honest, once a person has a vision for collaboration, I could collaborate with anybody, I am not limiting it.

From your project, Roadman and Folks, do you have any favorite song from it and why?

It’s quite difficult but I think one song that was the most sentimental for me, and that’s personal but it had levels to also have other people on it, was called ‘Flowers.’ Like I’m going to get my flowers. It was talking about my journey through the years. It’s the shortest song I have ever written in words, but in length it is definitely not short because of the instrumentation. But what Flowers spoke out for me was that we are doing these things. We are being independent. We are planting dreams. We are doing the work, and it’s only a matter of time. We are going to get our flowers. I am going to get my flowers. You are going to get your flowers. It looks like nothing is happening but something is happening. And it just slows in different ways, in the shortest possible way, in a soulful way. That was how I got the song. Another song on the project that was intriguing. There are actually three songs. Beyond Yakoyo, there was ‘Dumb Luck’, ‘Late Night on Lokko Streets’ that featured members of SuperJazzClub. ‘Sons of Beaches’, also. This is a song that talks about coastal living. You know, the nuances of living in the coastal part of Africa, Ghana, just the experiences I’ve had with my people, with my friends. And some of them can relate to these things. But ‘Flowers’ was one specific song that was down to my heart.

What are some of your favorite things to do when you are not making music?

Just living. The way I live is just like spontaneity. I can really just get up today to go to the mountains. It’s not in Abuja anymore, sadly because my parents are going to get a heart attack. I just live to travel, and I don’t mean entering the flight going to experience Europe or whatever it is or another country. I mean, it could be another country, but really just being spontaneous. Go to the mountain, go to the river, sit down, be by myself. This is one major thing I love to do, like ride my bicycle around town. Next year, I’m going to join a community of bikers in Agba. So, these are just some of the other things I like to do; go on road trips mainly.

What’s next for you after this project?

Well, I think I said it in one of the songs, what I am is more than I can ever plan. But one of the main things that this project is going to, I mean, looking at it, like I said before, I was originally meant to be a performing artist. So, one of the things I am going to be doing with this project, which I am already doing, is take it round, play in different countries, have it as a tour experience in different systems. I have set up already, and it’s going to happen again this year. We are going to take it on tour, go to different places. Beyond that, after this project, we are looking at an album. The album is already like 60 percent written. We’ve already started to work on it. I can’t tell you the name of the album yet, but these are the plans. Who knows what might happen. It might even be two or three albums. I can just pull Frank Ocean’s people. So, yeah those are the things that I think are next for me in the coming years or coming months.

What’s the vision for Tommy Wá?

Music is a beautiful thing for me, but I do not think my purpose stops at me just making music. My purpose is to create an Africa where the musicians, the artists are better served, where the relationship between the artists and their community, the people that listen to them, they have a seamless relationship. So, beyond me just making music as Tommy Wá, the benchmark of that is creating platforms for artists like myself, creating platforms for audiences to experience art beyond just the regular system that we have now. Adding literature to what is already there for

African music, you know Afrobeats and all these things. What of other genre forms, what if other forms of expression? So like the next couple of years, this is the vision for me. Beyond me just taking a pen to paper, writing music and all those things, I am beyond just a musician. I am an artist and all, in all ramifications. So, this is the vision for Tommy Wa, and my music is a yardstick. You know, you can’t give what you don’t have. So, my music is, let me know how to do it first, then I can teach other people. That’s the main goal for Tommy Wá.